|

|---|

Monday, June 8, 2009

Ultimately, photography is subversive, not when it frightens, repels, or even stigmatizes, but when it is pensive, when it thinks.

Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida 1980

I'm interested in photography. Some believe that photography is fundamentally different from other forms of representation. Roland Barthes happened to believe this and he made it the focal point of his short book, Camera Lucida, Reflections on Photography.

My mother owned this book by Barthes. I borrowed it from her many years ago. Her notes are still in the margins, scrawled every which way. To write this review, I retrieved the book from my library, attempting to gain some knowledge . . .

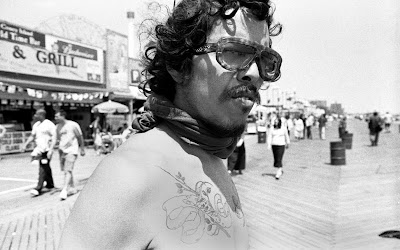

In all honesty, I don't know if photography belongs in a special category or no category at all. But the effect of certain images on me is beyond a doubt mystifying. And this was the case when I looked at the photography of David del Pilar Potes.

I'm going to try to recount my subjective experience. While surfing the Internet one night, I found this image:

A man sits beside a Banyan tree, reading. The primordial world hangs over him in luxurious, gargantuan branches.

At first I couldn't situate the image in my mind. That is, I didn't know exactly what I was looking at. The grotesque musculature of the tree trunk seemed to conceal the tree itself. And then I noticed a little man sitting beside the tree on a bench and a garbage can about ten feet away. As I scrolled the bottom bar, I witnessed a seamless collection of photographs nothing like this one, but all of them strangely connected.

For the rest of the night I tried to understand what it was about David's photographs that stirred in me such a visceral, intense preoccupation. Looking at them, my heart raced, and soon I needed to contact the artist and tell him that his photographs were producing this response in me. I would have to write a review of them; there was no choice. For the review, I would need to sample his images; how else could I convey to my readers the mystery behind these photographs?

The next day I returned to the pictures and studied them more closely. I wouldn't hear from David for another two days. At this point, I remembered the book by Barthes that I had inherited from my mother. I started reading it.

The studium speaks of the interest which we show in a photograph, the desire to study and understand what the meanings are in a photograph, to explore the relationship between the meanings and our own subjectivities. (1)Yes, I was interested in these images. What else could explain my "enthusiastic commitment" in Barthes's words? It was this interest that drew me back to David's website again and again.

The studium is a result of my volition, my will to study the photographs.

There was meaning in the photographs, but the sort of meaning you scooped up with your impressions and created yourself. There was no pre-existing meaning, only suggestions and possibilities, which made studying the images similar to looking at artifacts in a museum. You could play with the storyline of each object, invent the characters and their relationships, tease out the latent emotion of the scenes--

A teenager sprays graffiti on a concrete wall. How far is he from civilization? Or is this civilization?

You're looking at one of my favorite pictures by David del Pilar Potes. Again, we have the juxtaposition of the natural world and a single human being. A teenager is figured prominently in the foreground, but in more than half of the picture, the forest soars over the concrete walls.

We seem to be looking down into the mouth of the embankment. It's hard to identify exactly what or where the location is. Some place in the mountains.

The inability to situate the image, like with the Banyan tree photograph, provokes me. Barthes would say this detail "pricks" me. He calls it the punctum.

At first I think the teenager spraying graffiti also "pricks" me--or rather his vandalism does.

But then I realize that I'm not against the subject-matter. I connect with the youth who in the middle of nowhere scrawls his name on the wall. Although he's vandalizing property, it's not the vandalism that bothers me.

The concrete walls, the hollow embankment, bothers me. Ugly, massive, and intrusive. I would vandalize the walls myself . . .

Already, I've created some value, some meaning, for the teenager's act. This meaning gives the picture its wholeness. Not only does my private meaning forgive the teenager's act, but I also know that whatever is happening in this photograph, it is exactly how it should be.

The punctum (a Latin word derived from the Greek word for trauma) . . . inspires an intensely private meaning, one that is suddenly, unexpectedly recognized and consequently remembered (it "shoots out of [the photograph] like an arrow and pierces me”); it ‘escapes’ language (like Lacan’s real); it is not easily communicable through/with language. (2)These definitions are not taken from Camera Lucida. If I quoted from Barthes's text, it would shed little light on what I'm talking about. He has to be read in context. I'm relying on Kasia Houlihan's annotations of the book.

Her eyes are closed and she's pointing to infinity. The city smiles in the background.

David del Pilar Potes excels at describing humanity. The breadth of the subject-matter, the comprehensiveness of the photos, capture many different lives held together by a common spirit.

Potes says his "primary aesthetic is in documentary photography, focusing on people and landscapes." I scroll through each of the five collections on his site, discovering seascapes, rock formations, dolphins, fires, prophetic graffiti, dogs playing in a gully, solitary boats, theater performances, a couple in a diner, portraits of strangers, a motorcyclist in an empty parking lot, ethnic festivals, pictures of food, acrobats . . .

And you cannot pin down the photographer. He disappears into his work. He does not privilege spectacles over mundane aspects of life. He lovingly documents all. And when his arrangements do include photographs of the bizarre and fantastic, the pictures stand out as they would in real life. Because sometimes our world is purely odd.

More of David del Pilar Potes's photography can be found at his website.

More of David del Pilar Potes's photography can be found at his website.

0 Comments:

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)